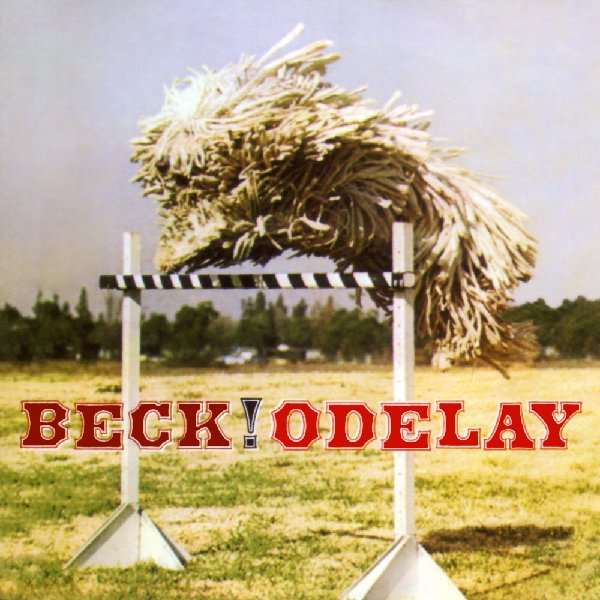

“The cover was my girlfriend’s idea,” Beck said of Odelay (shown right), explaining the artwork to KCRW’s Morning Becomes Eclectic the day after the album’s 1996 release. But what exactly is pictured on Odelay’s cover? Twenty years later many fans still can’t make it out. Was a mop-head tossed and a picture taken of it in mid-air? Is it some sort of hyper-meta-irony? An inside joke perhaps?

“She found it in a book about dogs,” Beck told KCRW. “It is a dog in fact. Don’t ask me why he’s jumping over a hurdle, but it’s beautiful.” He elaborated for his feature in the July 11, 1996 issue of Rolling Stone, “I was looking at this dog book and I came to a picture of the most extreme dog. He looked like a bundle of flying udon noodles attempting to leap over a hurdle. I couldn’t stop laughing for about 20 minutes. Plus the deadline for a cover was a day away.”

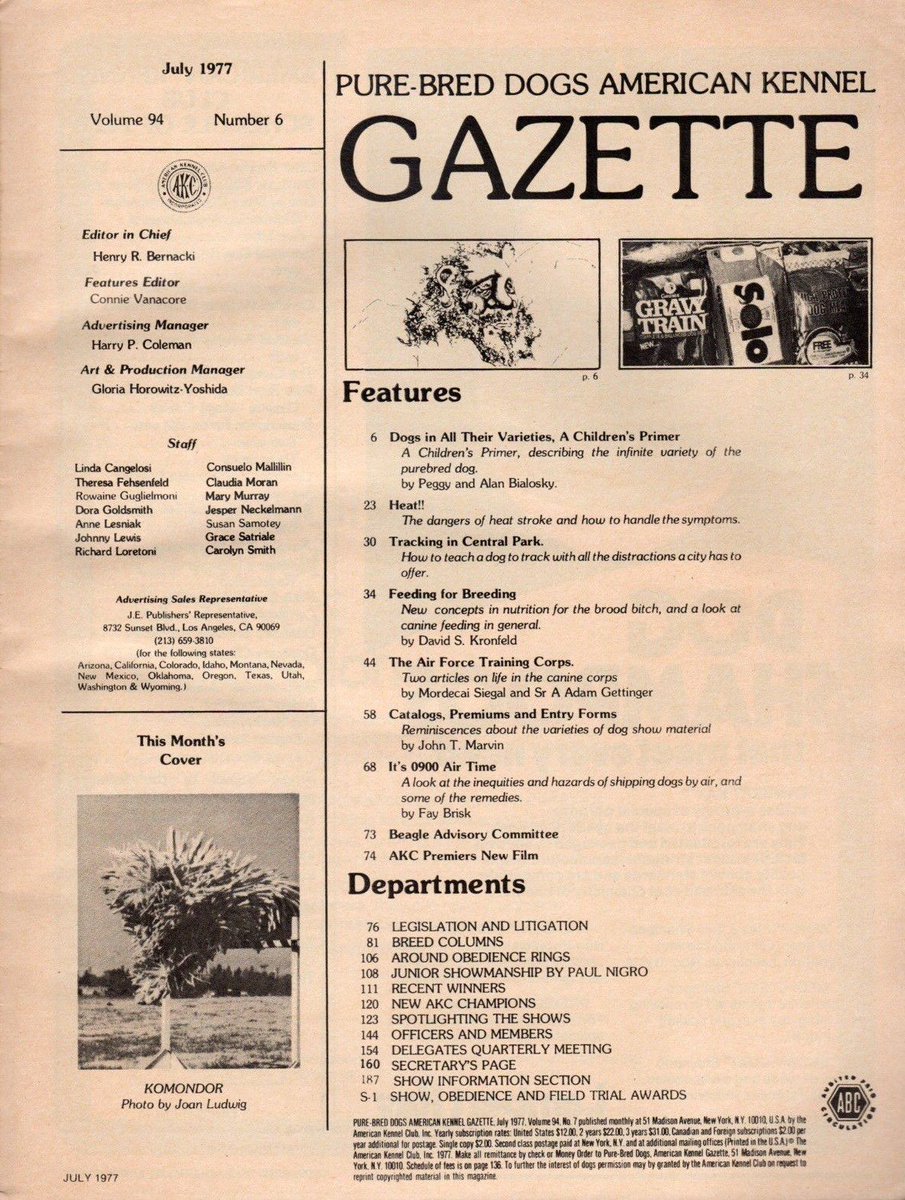

So there we have it straight from Mr. Hansen’s mouth: Odelay’s cover shows a dog jumping over a hurdle. But not just any dog: a Komondor, a breed sometimes referred to as “mop dogs” or “Hungarian sheepdogs” that are instantly recognizable for their long-haired, corded, mop-like coat. Odelay’s cover photograph was one of several that Joan Ludwig shot for the July 1977 issue of the American Kennel Club’s Gazette. The cover and opening page from that issue are shown below:

According to the American Kennel Club, Ludwig “reigned for a half century as the acknowledged West Coast master of canine photography” (read more about her work here). Her mop-dog shots, such as the one used on Odelay’s cover, were already known in the canine publication world before Beck discovered them. Of the album cover picture, The American Kennel Club writes: “probably the most widely circulated image in the Gazette collection was the brainchild of photographer Joan Ludwig (1914–2004), whose eye for the odd, the comic, the ironic was unmatched among her ringside peers.” The surreal image of the unidentified Komondor in mid-jump was reproduced in countless newspapers, books and magazines, in turn catching Beck’s eye much the way many of the sounds on the album had caught his ear.

The parts are borrowed but the whole is all original.

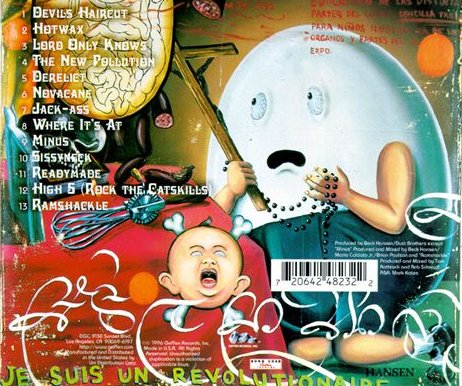

Odelay is filled with recycled riffs (right from the opening notes of “Devil’s Haircut,” built on the main lick from 1960s garage rock staple “I Can Only Give You Everything”), misplaced melodies (the “I get down” section of “Hotwax” is sung to the tune of “Jingle Bells” for instance), spoken word samples (“I’m the enchanting wizard of rhythm“), samples of drum grooves and musical accompaniments (“Jack-Ass'” atmosphere comes from Them’s remake of Dylan classic “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”), even a sampled scream, among other examples. It’s most famous though for its melding of multiple styles. Take “Sissyneck.” First there’s whistling, sampled from Dick Hyman’s 1969 novelty instrumental The Moog and Me. Then it cuts to a funky riff borrowed from “A Part of Me” by the 1960’s band Country Funk and mixed with a boogaloo drum pattern and a looping organ part on the upbeats sometimes claimed – perhaps erroneously – to be taken from the circus-like intro of Sly & the Family Stone “Life.” Given Beck and the Dust Brothers’ approach to sampling, is “Sissyneck” hip-hop? Is it country? Funk? Fairground music? Novelty music? Some sort of mutant Americana rock? The answer of course: none of the above, and all of the above – which partly explains its genius. By the time “Sissyneck’s” chorus rolls around the traditional country and western pedal steel licks are laid on so heavy we can practically see tumbleweeds blow by. Each of these elements retain the identity of the musical heritage from which they came, and yet the track as a whole is its own world, decisively uncategorizable, divorced from the cultural traditions it overtly references. Steeped in sounds that came before while ultimately sounding like nothing prior. The parts are borrowed but the whole is all original.

It’s not just “Sissyneck.” In one way or another, the same could be said of every track on Odelay. And of its cover, as well as the CD booklet’s images and design, and the music videos. For now we’re focused on the album art, and it’s only fitting a disc such as this – defined by Beck’s redefining of sounds and styles dug up from obscure records, literally and figuratively – would have a cover similarly dug up from a canine magazine that otherwise would have remained on the fringe of pop-culture.

Look carefully at the 1977 magazine cover however and you’ll notice it’s a different photo than the one Beck used. Apparently the picture that appeared on the 1977 Gazette cover (which shows the dog after its front was over the hurdle) was not the only shot. Rather, it was but one of many from a series that was republished for years to come. The one in the book that Beck spotted and repurposed as Odelay’s cover (which captures the dog before it had cleared the hurdle) is another shot. It also appears Joan’s original photo was altered for Odelay: the mountains in the backgrounds are gone, as are the clouds; the buildings are obscured; the grass less defined. How very Beck! Odelay’s cover isn’t just another republication, as with the dog books. It’s redefined into something fuzzy, much the way Beck deliberately added white noise and used lo-fi recording techniques to instill in Odelay a distinctive sonic pallet. Could it be the album cover is actually a picture of the picture? Whether Beck photographed Joan’s photo from his girlfriend’s dog book, or it was simply digitally altered, either way explains the grainy quality of the background compared to the clarity of the originals, as shown above (albeit in a slightly different shot than the album cover).

Joan’s photograph – and whatever distortions it may have gone under – are just one ingredient in this iconic cover. Just as no sample on the album stands alone – its genius is partly what each is sampled with and how they are recontextualized by that combination – the distorted photo is mixed with another element: that lettering! The typecast; the striking omission of lowercase; the lack of space between Beck’s name and the album title; the exclamation point in its place; the bold colors that equally contrast the photo, but clash with each other – all transform the photo into something else, something Beck. The picture by itself is surreal, but not necessarily unique. In the context of a book of dog pictures, it’s to be somewhat expected. It is after all a picture of a dog, however amusing. But distorted, recontextualized and mixed with that lettering, it’s as idiosyncratic as the the collage of sounds and styles it visually represents. Beck’s use the dog pic is so out of place, many fans can’t even tell if it is a dog – much like the samples within that are brilliantly out of place, Franz Schubert’s “First Movement: Allegro Moderato” in “High 5 (Rock The Catskills)” for instance.

This dada-esque, remix/recontextualize approach is applied even more so to the CD book foldout, as well as the back cover, both shown below. The booklet artwork was conceived and collaged by Beck himself, along with Robert Fischer, and relies on original art by Beck’s grandfather Al Hansen, formerly a member of the 1960’s Fluxus art movement. Beck told KCRW, “We used pieces of his [Al’s] art. It’s a bit of his art [with] also this other painter Manuel Ocampo who’s a Filipino painter.”

Manuel “was originally going to paint, do all of the artwork,” Beck explained, “but we just used bits and pieces of his paintings in the collage inside and threw a couple of pieces of my grandfather’s, and I did a couple of drawings, and a friend of mine named Zarim [Osborn] did a a painting as well. Kind of an all-original collage.”

Manuel “was originally going to paint, do all of the artwork,” Beck explained, “but we just used bits and pieces of his paintings in the collage inside and threw a couple of pieces of my grandfather’s, and I did a couple of drawings, and a friend of mine named Zarim [Osborn] did a a painting as well. Kind of an all-original collage.”

Which explains why the visuals so perfectly match the music they package, music that could after all be summed up as “kind of an all original collage.”